Zelda is back in people’s minds again with the recent release of “Tears of the Kingdom” - the fastest selling Zelda game of all time. I haven’t started playing that one yet as I have only just started the previous game, “Breath of the Wild”. Not just that, I have been playing a much older Zelda game a lot.

By “a lot” I mean over and over and over…

… And Over And Over Again

I used to occasionally watch speed runs of games on YouTube, those where the players attempt to complete the game as quickly as possible. This is more out of curiosity than any sort of appreciation of the skill, such as absurd examples like a player completing Final Fantasy VII in less time than the sum of the requisite unskippable content1.

Inevitably the algorithm started throwing videos at me, but it was all the same type of content in which a player had spent hundreds of hours optimising their execution of the game controls to a point it’s almost subconcious. This kind of stuff, while impressive, is tedious.

However, the algorithm did throw one particular suggestion at me that I found interesting: “A Link to the Past by Andy in 1:14:58”. This one showcased all sorts of ways the game could be broken by inputting specific movements and/or frame-perfect timing2.

I had fond memories of this game from my childhood, and because I watched that video in its entirety the algorithm started throwing more at me that piqued my interest further.

A Link to the Past

The third game in the Zelda series, “A Link to the Past” was released in Europe in late 1992. I saved up many weeks of paper round money to eventually purchase a SNES and the game in the summer of 1993. I then spent the rest of the summer completing it, which requires the following steps:

- Storm the castle to rescue Zelda

- Collect the three pendants

- Get the master sword to defeat Aga

- Get transported into the dark world

- Where you collect seven crystals

- Which frees seven maidens

- To break the seal on Ganon’s tower

- So you can defeat Ganon

- Saving Hyrule 🎉

A Link to the Past is a relatively linear game. You get items out of chests or other locations, and these progression items are in the same places every time you play. It’s entirely deterministic. The game opens up as you collect these items - you can’t access certain parts of the world until you have the flippers, hammer, bow, and other key items.

While the vanilla game has a set route to completion, there are some randomised aspects such as enemy behavior and some non-progression items. Because of its linear nature, people began speedrunning it - trying to complete the game as quickly as possible. Over the years, the completion time has dropped to about 1h20min.

Keep in mind that it took me an entire summer to complete the game, while speedrunners can now do it in less than an hour and a half. Personally, I don’t find speedrunning the original game particularly interesting because it’s essentially a grind; you just keep playing it repeatedly, resetting when you make a mistake.

Like I said above, I find that kind of thing tedious.

A Random Encounter

The algorithm continued to throw content at me, and most of it I slapped away - as much as is possible that is, such is the nature of these content providers. No, I don’t want to watch another video on the same tired subject. No I don’t need to see recommendations for hundreds of vacuum cleaners because i just bought one. That sort of thing.

But the algorithm persists in the hope that something will catch my attention.

Sure enough that happened with a video showcasing The Randomiser3.

The Randomiser?

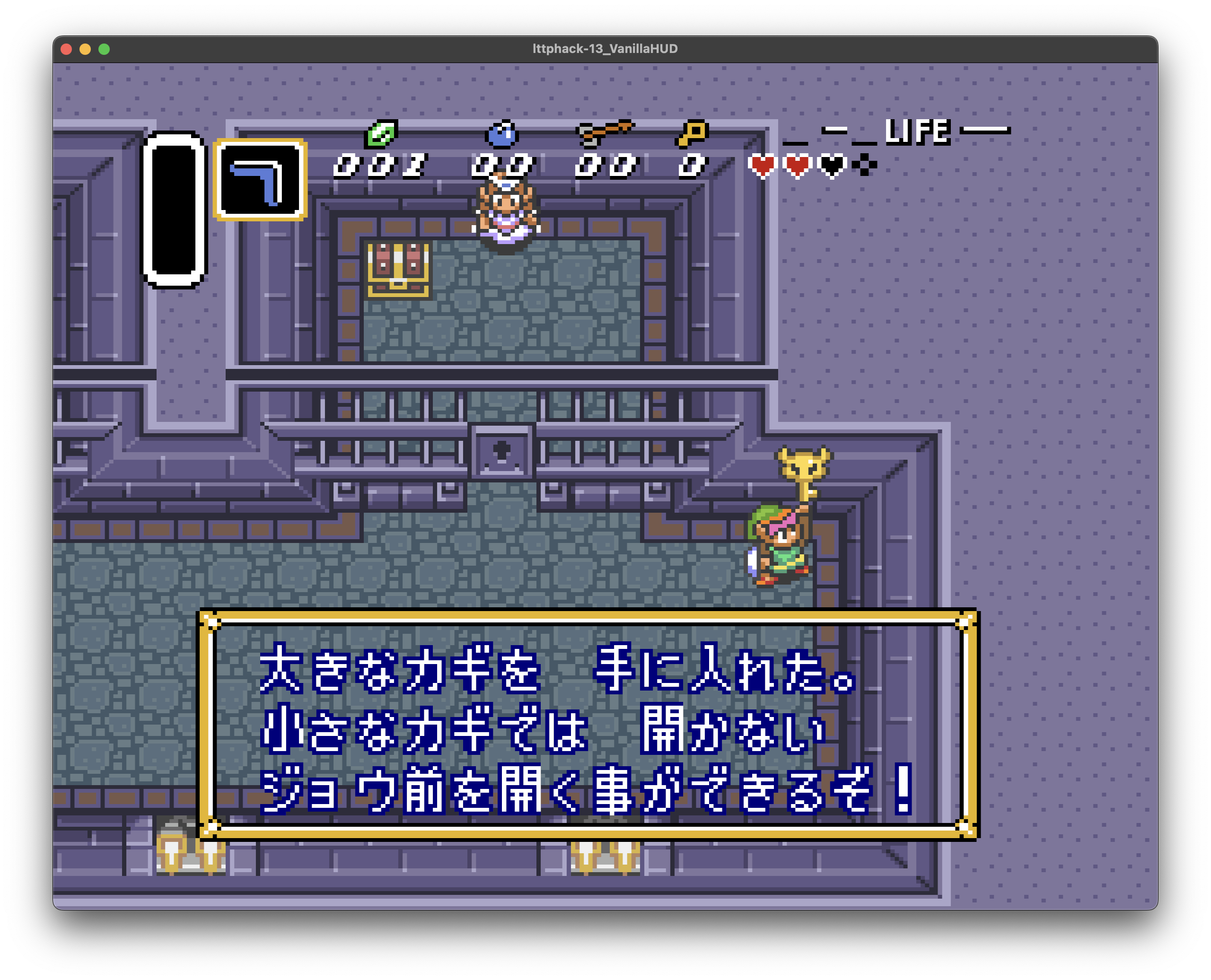

A patched version of A Link to the Past where all the items are shuffled. In the original game there are 216 items, with about 20 of them granting progression. By shuffling these items the randomiser changes the possible routes through the game, effectively creating infinite variations.

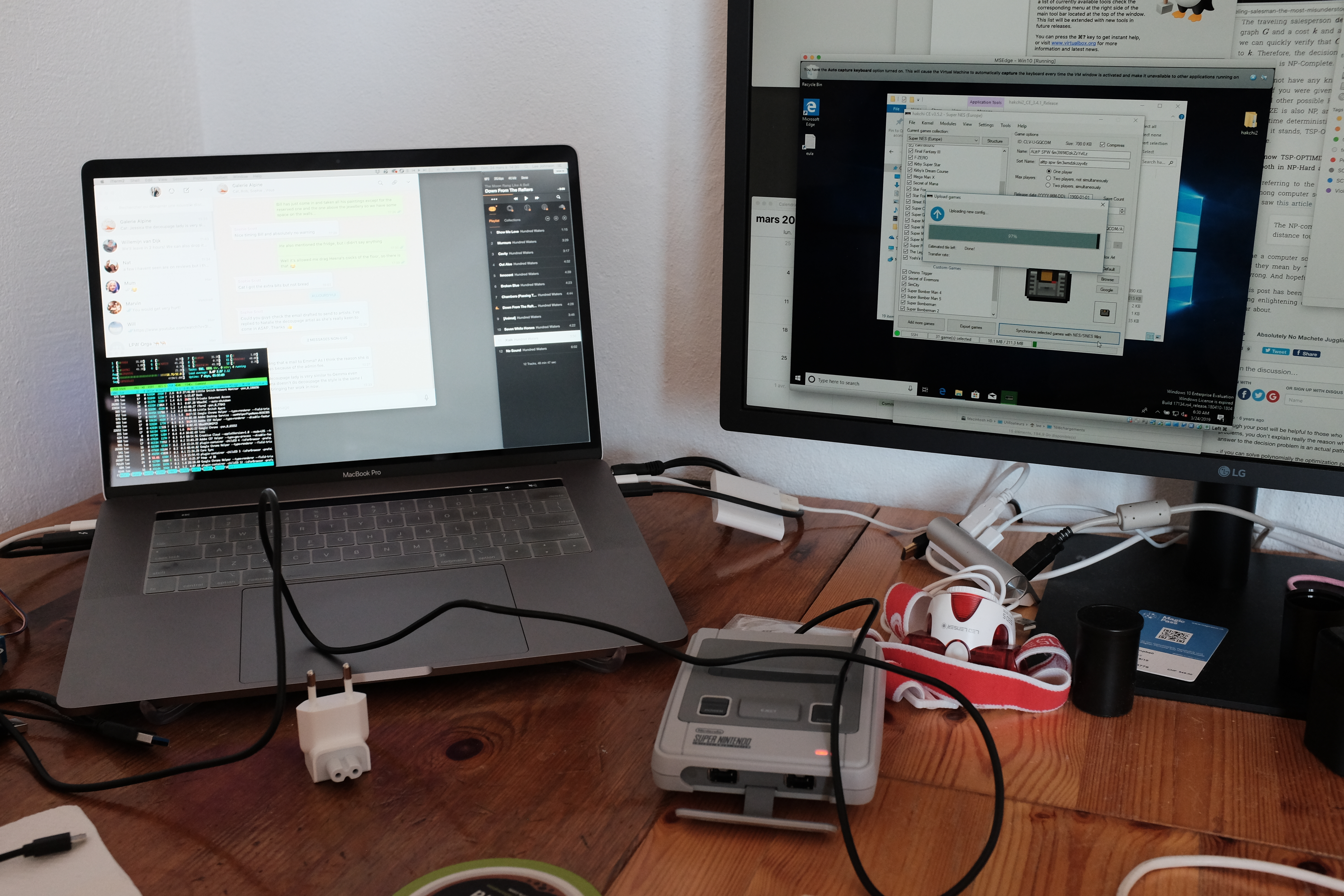

I started playing The Randomiser in late 2018 after realising it was possible to patch a mini SNES classic through various combinations of hardware (emulation) and software. This allowed me to play the game while sat on my sofa with a controller, as I didn’t want to sit in front of my laptop to play it. The steps required to do this were a bit of a faff, given I use a Mac, but it worked well enough.

My first playthrough of the game, which was a good twenty years since I had last played it, took 6 hours. Eventually I got good enough at it to complete most seeds (randomly generated games) in under 2 hours. An experienced player can complete most seeds in about 1h30min.

The randomiser itself understands the game’s logic, preventing “hard locks” - situations where an item would be placed in a location that requires that same item to access it, which would make the game impossible to complete. It has sophisticated logic built into the code to prevent these situations.

The randomiser has been around for about a decade now, and it’s evolved beyond just randomising item locations. It now allows different modes of randomisation, changing not just where items are placed but also what tasks you need to complete, what enemies you face, where bosses appear, and much more.

In a randomised game, you might not need to storm the castle to rescue Zelda, collect the three pendants, or defeat Agahnim. Getting transported to the Dark World remains a requirement, but rescuing the seven maidens might be optional before climbing the tower to defeat Ganon and save Hyrule.

This makes the game far less linear, and what’s particularly interesting is that you might complete certain requirements without realising you didn’t need to. Inevitably people started speedrunning the randomiser, which becomes fascinating because you’re trying to figure out the quickest way to complete something that you don’t yet know how to complete.

Technicalities

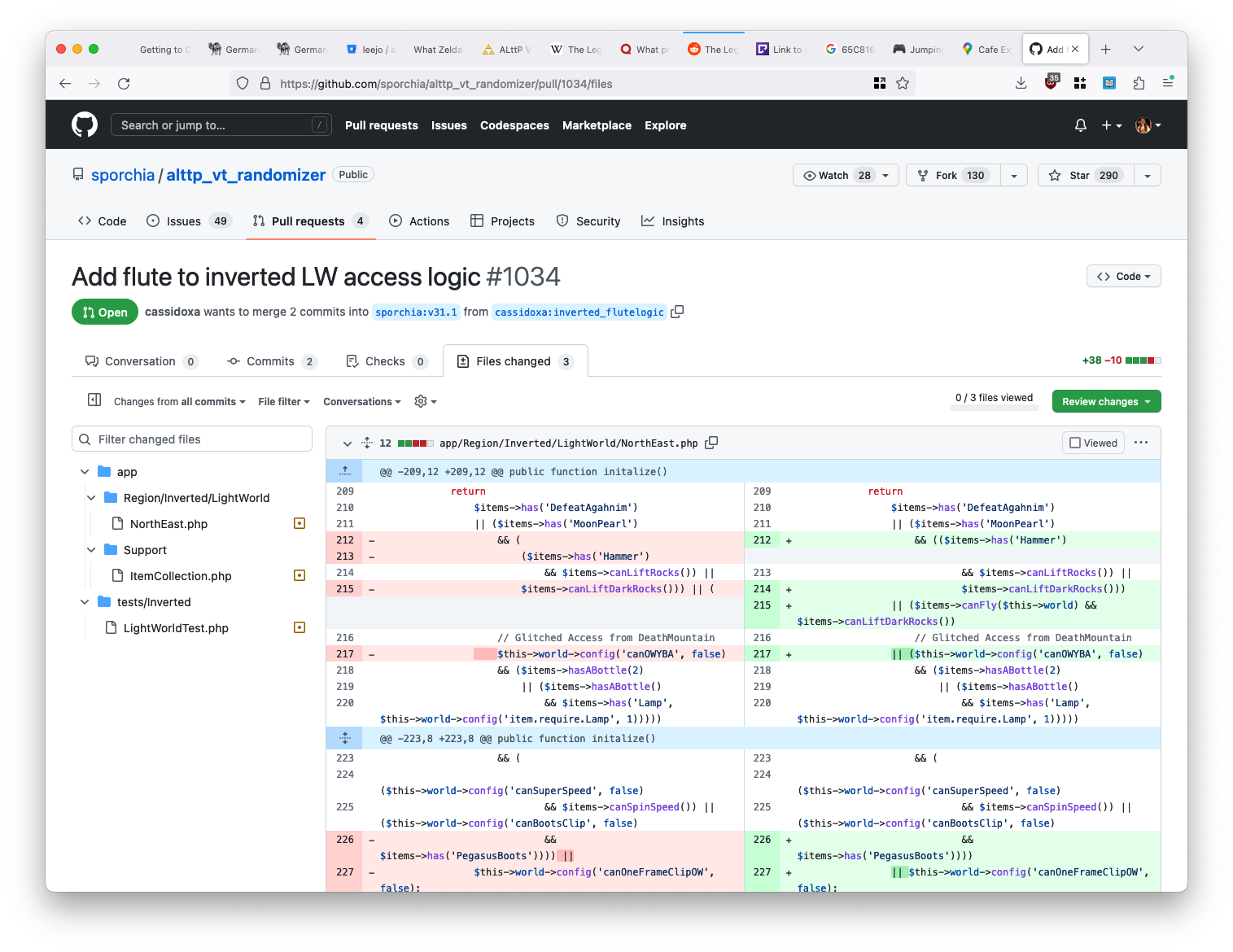

The randomiser was originally written in C# but has been developed in PHP since 2016 (that’s the initial commit date, so it probably predates that). It’s currently on version 31, with version 32 in preview.

At its core, the randomiser knows the address space of every item in the game and the logical requirements to access those items. Take Checkerboard Cave, for example. In the vanilla game, this location just contains a heart piece - not essential for completion. But to reach it, you need four or five progression items. In the randomiser, the item in this location could be almost anything, and you might acquire the necessary progression items very quickly.

From a coding perspective, the randomiser tracks the ROM address of each location and maintains a location collection with information about that location. It also encodes the logic of how to access each location. For example, to reach Checkerboard Cave, you need to be able to lift rocks, have the magic mirror, and access the region where the cave is located. That region itself will have its own set of requirements.

The very last location in the game, at the top of Ganon’s Tower, requires almost every progression item to reach.

The Attraction?

What makes the randomiser appealing is that every new seed is different. With about 20 items needed to beat the game and 216 possible locations where they can be placed, the challenge becomes determining how to reach these locations in the optimal order.

This creates interesting routing and logic problems. It’s essentially a variant of the traveling salesman problem (or “traveling Link” in this case), which is an NP-hard routing problem. But it’s actually more complex because certain areas only become accessible after acquiring specific items, and you don’t know where those items are.

So we’re adding known unknowns to an already NP-hard problem. The route evolves as items are accessed, including dead ends and backtracking. You might enter a location that has nothing useful and doesn’t grant any progression.

The randomiser’s algorithm is quite simple in concept. It shuffles all the locations and then goes through each one, placing an item and checking if it’s logically possible to place that item in that location given the placement of all other items. Every location knows the prerequisites needed to access it.

But solving the optimal route? That’s where the fun comes in - you never know what you’re going to get.

The Community

A huge community has built up around the randomiser over the 10 years it’s been around. There are Discord servers with thousands of users online at any time. People have created practice ROMs so you can develop your strategies, applications to keep track of what you’ve found and where you’ve been while playing the game, and even platforms for racing against other players.

There are podcasts (over 150 episodes of a bi-weekly show amongst others), development communities (the code is all on GitHub), and many streamers on Twitch. I have my own Twitch channel where I used to play once or twice a month.

One practical application that’s emerged is that people who weren’t previously interested in coding have gotten involved in the development community. The randomiser has also spawned similar projects for other games - there are randomisers for Metroid, Super Metroid, and even newer games like The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild.

Interestingly, due to some quirk in the ROM structure, you can even combine A Link to the Past and Super Metroid randomisers, allowing items from one game to be found in the other.

Converging Towards Execution

No community is immune from fracture, trivial or otherwise, and that happened recently with a patch to the randomiser to remove “lag”. Enabling the “fast ROM” feature that was originally excluded by Nintendo as a cost-cutting step.

The reality is that the racing aspect of the game has been converging towards execution for the last three or four years, and this was another step in that direction: levelling Hyrule’s playing field.

Knowing tricks, glitches, optimal ways to move through parts of the game and not bleed time is what wins you a race these days. So when the game was tweaked, breaking some player’s muscle memories, they weren’t happy about that.

To be good at racing you need to have excellent game knowledge, only gained by playing it a lot. Then you need to have excellent execution, only gained by deliberate repetitive practice of every possible scenario you might encounter. A thousand tiny optimisations. A few frames here and there, a second or two there and here. Rinse and repeat until you can do it without thinking. A grind.

And the randomiser has become a grind, the races a showcase of execution, and the change to fast ROM merely highlighted this fact. The game being a grind? I don’t find that interesting, so I no longer watch races and now rarely play the game. In fact I haven’t played the game in over a year, which is why this post sat in my drafts folder for so long.

Perhaps the algorithm will throw something else of interest at me?